These lines come from an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s Ian Johnson that “China Beat” ran at the end of January, back when our site was still young (now that we’ve been going for more than a third-of-a-year, we hardly count as youthful anymore, so quickly does the blogosphere change). He was responding to a question Nicole Barnes had put to him about what he’d like to see more of from academics in Chinese studies, and he went on to specify that the problem lay primarily in how much jargon popped up in scholarly publications—though I suspect that he also might have been thinking about stodgy writing but was too polite

to add that.

to add that.Well, Ian, I hope you're reading this, as I have some good news, which may be especially welcome with Father’s Day coming up soon: Harvard University Press has released the U.S. edition of Geremie Barmé’s The Forbidden City, and it's just what the doctor ordered. It's a wonderfully readable, smart look at "The Great Within" (as the Forbidden City's sometimes called), which is jargon free and definitely non-specialist friendly.

It's also anything but stodgy. There are tales of court intrigue. And even a racy extract from a unpublished early-twentieth-century work by the renowned and then later reviled "displaced Cornish aristocrat Edmund Trelawny Backhouse," a famous Sinologist and forger, who claimed to have had erotic encounters with Empress Dowager Ci Xi, one of the most infamous residents of the Forbidden City, though, as Barmé notes, her reputation is not quite as bad these days among scholars as it once was.

The Forbidden City, tells intellectually curious tourists, as well as those with more specialized concerns (scholars, journalists, or, say, someone with a son who covers China for a major American newspaper) everything they might want to know about Beijing's biggest and most storied landmark. First published by Profile Books in the U.K. a few months back, it's short and beautifully packaged, with nice photographs and drawings inside and different but equally classy covers on each

edition. And it doesn’t require having a copy of the OED handy (to look up esoteric terms) or a doctoral degree under your belt (to figure out the theories invoked). Perhaps Barmé’s most accessible work to date, it still contains the mix of wit and erudition that China specialists have come to expect from all of his writings.

edition. And it doesn’t require having a copy of the OED handy (to look up esoteric terms) or a doctoral degree under your belt (to figure out the theories invoked). Perhaps Barmé’s most accessible work to date, it still contains the mix of wit and erudition that China specialists have come to expect from all of his writings.In a minute, I’ll have some additional things to say about what I learned from and like about The Forbidden City. I’ll also explain why I’m not a completely unbiased fan of the book, which is the first China-themed publication in a great series called “Wonders of the World” that is the brainchild of the multitalented Mary Beard, a prolific scholar of the ancient Mediterranean who among many other things writes a popular blog, “A Don’s Life,” that’s hosted by the Times Literary Supplement or TLS, for which she serves as Classics editor. Before getting to those things, though, I want to digress and talk about a recently deceased cinematic celebrity who has a curious link to the Forbidden City’s place within Western popular culture. No, I’m not thinking of Bernardo Bertulucci of “The Last Emperor” fame—as he’s still alive and well, as far as I know. I mean, instead, Charlton Heston.

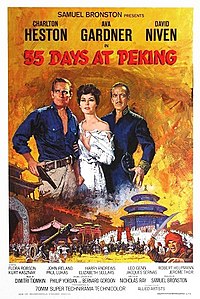

What exactly does this actor who died in early April have to do with the Beijing landmark that was home to figures like Last Emperor Pu Yi and Ci Xi? If all you went by the obituaries I’ve come across, you might be tempted to answer: Nothing. These overviews of the life and career of the actor-turned-anti-gun-control-activist typically focus on Heston’s political activities (from his youthful left-of-center leanings to the abrupt right turn that made him a spokesman for the National Rifle Association) and the parts he played in films that won awards (“Ben Hur”), inspired sequels (“Planet of the Apes”), or made an indelible mark on the American psyche (the cannibalistic classic “Soylent Green”). What I associate with Heston’s name above all, however, is “55 Days at Peking,” in which the Empress Dowager is memorably portrayed as an embodiment of pure evil. It’s the only Heston movie I’ve watched more than once, as well as the only one I've shown excerpts from to students.

What exactly does this actor who died in early April have to do with the Beijing landmark that was home to figures like Last Emperor Pu Yi and Ci Xi? If all you went by the obituaries I’ve come across, you might be tempted to answer: Nothing. These overviews of the life and career of the actor-turned-anti-gun-control-activist typically focus on Heston’s political activities (from his youthful left-of-center leanings to the abrupt right turn that made him a spokesman for the National Rifle Association) and the parts he played in films that won awards (“Ben Hur”), inspired sequels (“Planet of the Apes”), or made an indelible mark on the American psyche (the cannibalistic classic “Soylent Green”). What I associate with Heston’s name above all, however, is “55 Days at Peking,” in which the Empress Dowager is memorably portrayed as an embodiment of pure evil. It’s the only Heston movie I’ve watched more than once, as well as the only one I've shown excerpts from to students.I was disappointed, but hardly surprised, by the decision that obituary writers made to skip over this 1963 release that deals with what’s generally called the Boxer “Rebellion”—a somewhat problematic term, as many readers of this blog know, since the anti-Christian insurgents involved were odd sorts of “rebels,” often expressing support for and sometimes being backed by the Qing Dynasty. Bringing the film into their Heston obituaries would have allowed the obit writers to point out that this movie gave the actor a chance to share the screen with Ava Gardner, who played his Russian love interest, and with the dapper David Niven, who played a British participant in the multinational group that saved the day by defeating the Boxers. It would also have let them point out that, like James Dean, Heston once took direction from Nicholas Ray, who was best known not for “55 Days at Peking” but for a very different sort of “rebellion” picture: “Rebel Without a Cause.”

Still, the oversight was natural enough. It's true that the film is still shown from time to time on cable television stations, presumably because of their desire to cater to war-buffs and history-buffs who don’t mind it when a picture runs a bit long, as this one does, and has patches of dialogue and scenery that seem a bit cheesy, to put it kindly. But “55 Days at Peking” is of much more interest now to Sinologists than to cineastes and probably holds most appeal of all to those intrigued by the many ways that Cold War politics put their stamp on mid-to-late 20th century representations of historical developments. It is no accident, for instance, that American military man Heston and Niven’s main Japanese counterpart in the multinational anti-Boxer force comes off much better in the film than does their main Russian ally.

Even though I wasn’t surprised that obituaries ignored the film, I definitely would have been surprised if had Barmé had left “55 Days at Peking” out of his new book. After all, some of the film’s action takes place in the Forbidden City—or, rather, in a Madrid mock-up of this site (the real thing wouldn’t be the setting for a big budget foreign feature film until Bertolucci used it to such powerful effect in the 1980s). And Barmé’s not the kind of person to shy away from mixing scholarship with pop culture savvy, as shown, for example, by his allusion to a Hollywood film involving puppets in his scathing China Journal review of Mao: The Unknown Story.

Moreover, openness to mixing pop playfulness with serious points about famous landmarks has always been an appealing feature of the “Wonders of the World” series. This was demonstrated in The Parthenon, the first book in the series. Written by Beard, it opens with an amusing quotation involving Shaquille O’Neal (asked by a reporter if he went to "The Parthenon" while in Greece, he allegedly responded that he'd been to so many clubs that he couldn't remember all their names) and discusses a computer game inspired by the Elgin Marbles controversy.

Having just finished The Forbidden City—fittingly enough on a plane flight to Athens, en route to a conference on the upcoming Beijing Games, convened at the International Olympic Academy in ancient Olympia—I’m happy to report that “55 Days at Peking” is indeed one of the many Great Within-related texts that Barmé dissects. And, better yet, after reading his account, I’ll never again look at the movie, which I thought I knew well already, in quite the same way. I learned new things about the previous roles played by one of its stars: the actress who did such a diabolical turns as the Empress Dowager had previously channeled Catherine the Great on screen. And while I was aware before of the liberties the film took with historical actors (the Boxers come off a lot like the villains in old Cowboys and Indians Westerns), I’m now much clearer about the specific changes it made to the physical and sacred geography of Beijing (placing buildings that are actually far apart right by one another and so forth).

More importantly—as I realize the Heston film is a personal obsession of mine that is not necessarily shared by all readers of Barmé’s book, or this blog, for that matter—“55 Days at Peking” is only one of a long list of things on which The Forbidden City sheds new light. The book is filled with insightful comments about art and architecture and about how China’s politically tumultuous mid-to-late twentieth century affected what was done in and to the Forbidden City, a topic previously explored in an illuminating fashion in a special issue of a Barmé-edited online journal, The China Heritage Quarterly. It also contains a wonderful chapter that, drawing with full acknowledgement upon a very special Chinese book on the subject, tries to recreate the activities of a Qing Emperor on a “typical” day.

As I said before, though without explanation then, I came to the book as a far from impartial reader. Not only are Barmé and Beard both friends, but I actually put the latter in touch with the former when she mentioned looking for someone to do a China book for her series. (I can acknowledge that with pride now, having seen how well my foray into serving as a comprador of the publishing world worked out—and because Barmé is nice enough to mention it himself in the book’s “Acknowledgements” section.) But it is hard for me to imagine how anyone interested in Beijing, whether casually or for professional reasons, could come away from this book unimpressed—even if they had never before even heard of the Australian author, let alone read earlier noteworthy works of his, such as Shades of Mao, In The Red, and An Artistic Exile.

The Forbidden City is, finally, a book of great value even to those who care far less about Chinese buildings than they do about Chinese politics, and more about the contemporary scene than about Qing history. This is because, along with its other virtues, it provides, via comments scattered throughout its pages, the best account I’ve seen to date of an enduringly important and complex present-day political issue. Namely, the parallels but also the crucial contrasts between the modes of rule and styles of life of Mao and other Communist Party leaders, on the one hand, and imperial rulers and emperor wannabes like Warlord Yuan Shikai, on the other.

I don't know if any journalist will actually end up giving this book to a father for Father’s Day this year--or a mother for Mother’s Day next May. But I do know that, because of its nuanced handling of issues such as that just mentioned, it should be required reading for any journalist bound for Beijing.

1 comment:

Great review. I am going to order the book and watch the movie, almost certainly in reverse order.

Post a Comment