Wang Lixiong and progressive democracyThis essay continues the discussion of Wang Lixiong's work begun in Part I, which ran at China Beat

on March 9, 2009.By Sebastian Veg

Having analyzed the issues of colonialism, cultural rights of Uyghur populations, and the question of a Han nationalist revival, Wang Lixiong concludes the book by three “letters” to his Uyghur friend Mokhtar, in which he reframes the discussion on Xinjiang within his more general ideas on political reform in China. His reluctance to consider Xinjiang as “different” from other regions in China (while he is less reluctant to do so in the case of Tibet) is not unproblematic; nonetheless his voice is important because he is a critical intellectual “on the edge” who has visibly not entirely renounced influencing the debate in Beijing policy circles.

Wang Lixiong has some deep-set doubts, both about the practicality of independence as a goal for Xinjiang (due to the presence of a large Han population and their control of resources), and about what he calls “large-scale democracy”. In another text, he expresses his agreement with a draft Constitution prepared by a group of dissidents (Yan Jiaqi and others), under which Tibet would receive a high degree of autonomy and the possibility to determine its own status after 25 years, while Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia would only be granted the status of autonomy through a two-thirds vote in the National People’s Congress.

[1]While Wang insists that he doesn’t mind one way or the other whether Xinjiang becomes independent, he emphasises alternatives to independence: the guarantee of genuine religious freedom, and the possibility of controlling labour migration by a work permit system that would apply to “cultural protection zones” (including Tibet), and which would serve to prevent desertification, degradation of the environment, and growing water shortages (p. 439). For Wang, democratisation in China, as opposed to a higher degree of autonomy, might be prone to nationalist manipulation and internal fracturing. He therefore calls for an embrace of the Dalai Lama’s “Middle Way” of a high degree of autonomy within the framework of a federal China, going so far as to propose that the Dalai Lama become the chairman of a provisional government.

Nonetheless, his three “letters to Mokhtar” reveal some of the contradictions underpinning his thoughts on political reform in China. The first letter, devoted to terrorism, is very much in the apocalyptic mode of his science-fiction novel

Yellow Peril. In his second letter, he insists on Chinese nationalism. For Wang, China did not experience the nation-state model before 1911, and at that time its first formulation included Xinjiang and Tibet in Sun Yat-sen’s “Republic of five races” (Han, Man/Manchu, Meng/Mongolian, Hui/Muslim, Zang/Tibetan). He adds that nationalism has always been an essential part of CCP ideology, and now the only portion remaining. For these two reasons he believes that democratisation would not necessarily solve the nationality question (p. 444).

Whereas the Soviet constitution, no matter how misused, originally foresaw regional autonomy on paper by virtue of its federal nature, Wang asserts that no similar provision exists in the PRC Constitution, and that as a result, if China began unravelling, there would be no framework to stop the process from spreading to Guangdong or Shanghai. Conversely, he worries about an independent Xinjiang continuing to break down along ethnic lines into myriad autonomous micro-states, underlining that Uyghurs represent a majority of the population in only about one third of the territory concentrated in Southern Xinjiang, where there is no oil and resources. He wonders about the rights of the Hui (although one could easily object that there are Dungan populations in most of Central Asia), and highlights that Tibet, by contrast, is practically a mono-ethnic area. This is somewhat troubling, as in his articles on Tibet Wang argues against the viability of Tibetan independence, despite its ethnic homogeneity, on the grounds that the small Han elite controls the most productive sectors of the economy and the most dynamic groups in Tibetan society (“Zhuceng dijin zhi”,

art. cit.).

Wang’s assertion about the lack of a legal framework is not quite true: China’s Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy (

Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Minzu quyu zizhifa), revised in 2001 and largely disseminated though a 2003 State Council White Paper on the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), could provide a legal framework for autonomy (though not for secession, like the Soviet constitution), even though it clearly remains a political fiction at the present time (as was the Soviet constitution).

[2] More largely, within the context of the international conventions ratified even by the present Chinese government, as well as other international declarations, a stable body of norms regarding minority rights and rights for indigenous populations would be available to guarantee either substantial autonomy for Uyghurs within China, or for Han within an independent Xinjiang. In this respect, Wang Lixiong seems to remain captive to conventional views in China that describe international covenants as instruments of power play: he describes them as merely a pretext for American or Western intervention in Xinjiang aimed at destabilising China, and quotes the theory of “precedence of human rights over sovereignty” or

renquan gaoyu zhuquan.

His third letter deals with his system of proposed “progressive democracy” (

dijin minzhu) and the implicit critique of liberal democracy it contains. Wang calls the latter “forum democracy” (

guangchang minzhu, p. 457), and believes it can only exacerbate interethnic tensions, which will be fanned by the elite, a phenomenon not unknown in “mature democracies” (he cites support for the Iraq war). “Large-scale democracy” (

daguimo minzhu) will polarise political debate and lead straight to fascism (p. 460), as opinion leaders in Xinjiang will want to settle scores with China, the media will pour oil on the fire to make money, and the “masses,” who love heroes and lofty speeches, will follow populists and opportunists.

Nonetheless, he sees democracy as the key to resolving ethnic conflicts, the problem being not democracy itself but “large-scale democracy.” Therefore, Wang goes over old ground by proposing a system of indirect elections, based on natural villages, in which votes would take place by household, each household selecting one representative (one wonders how women would fare in this system of representation), thereby allowing for direct deliberative democracy by consensus. The elected representative automatically becomes a voter on the higher level, and so on, preserving the direct and participatory nature of democracy (p. 464). In fact, this blueprint clearly reveals Wang Lixiong’s misgivings about representation and vote by majority. He favours consensus over voting, pointing out that all elections are problematic, even in the United States (the 2000 presidential election inevitably comes up), not to mention in a Tibetan village in which a majority of inhabitants are illiterate.

Although he writes that in this system policy decisions on various levels should not interfere, he gives no guiding principle, not even a philosophical one, to explain how responsibility should be divided. The implicit assumption is, in fact, that voters are not qualified to deal with any matters beyond their immediate experience, and that the only decisions taken on each level are those that directly affect the life of the constituency. “Regarding larger matters that go beyond the borders of their immediate experience, it is very difficult for the masses to gain a correct grasp” (p. 466). This is a highly elitist system, the most worrying aspect of which is that it relies on the spontaneous generation of a social elite to foster democracy, rather than on an institutionalised system of checks and balances. Although Wang insists that this system will ensure that China does not break apart by guaranteeing both autonomy and cohesion (p. 468), one cannot help but wonder whether China and Xinjiang would not be better served at the outset by a full implementation of China’s own Autonomy Law, to be completed by other guarantees of the rights of minorities as set out in international laws and norms. Interestingly enough, while he is so wary of representative democracy, Wang Lixiong entirely trusts his own electoral system to guarantee individual and collective rights by its intrinsic mechanisms rather than by formalised norms (p. 469).

For these reasons, although Wang Lixiong has gone further than most Chinese intellectuals in exploring the rights and claims of ethnic minorities and how they fit into the political problems of China as a whole, this book remains somewhat disappointing. It is true that he paints a sympathetic portrait of “ordinary Uyghurs,” far removed from the usual clichés of official discourse, exoticism, or commonly repeated slurs -- an important accomplishment that may act as bridge towards even-minded ordinary Han Chinese citizens. But just as he portrayed Tibetans as prone to blindly following Maoism as a new religion during the Cultural Revolution, smashing their own temples and Buddhas, and then blindly reviling Mao when he proved not to have been a god after his death,

[3] his view of Uyghur intellectuals as influenced by terrorism and Islam seems excessively culturalist in relation to modern, secular Xinjiang. His analyses of several issues appear uninformed. Leaving aside academic research, he is weak on government policy; a close reading of Hu Jintao’s readily available 2005 speech to the State Commission on Ethnic Affairs could have yielded important insights: one of Hu’s central tenets is that any form of increased autonomy remain subordinate to the “three inseparables.”

[4]Nonetheless, Wang’s openness to dialogue and public discussion of his ideas, without any taboos or prerequisites, is an important step towards weaving the concerns of Uyghurs or Tibetans into the debate on the democratisation of China -- taking into account, of course, that the present book cannot be published on the mainland. In this capacity, as also demonstrated by his March 2008 initiative on Tibet, Wang Lixiong is one of the closest examples of a public intellectual in China. In this context, his writings also demonstrate that, despite what the Chinese government publicly states, there is no consensus in China over the fact that no price is too high to ensure that the CCP remains the dominant force in Xinjiang or Tibet. His ideas may even trickle, gradually and windingly, to the corridors of power. Wang Lixiong opposes independence for both Xinjiang and Tibet, but his willingness to discuss practical measures such as migration restrictions or enhanced religious freedom also serves as a reminder that Chinese intellectuals are not necessarily Han nationalists.

Part 2 of 2.The full text of this review essay is published in China Perspectives, no. 2008/4. The author is a researcher at the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China. [1] Wang Lixiong, “Zhuceng dijin zhi yu minzhu zhi: Jiejue Xizang wenti de fangfa bijiao” (A Successive Multilevel Electoral System vs. a Representative Democratic System: Relative advantages for resolving the Tibet Question ),

http://www.boxun.com/hero/wanglx/6_1.shtml (19 September 2008).

[2] The Autonomy Law is available on

http://www.gov.cn/test/2005-07/29/content_18338.htm. See also: Information Office of the State Council, “History and Development of Xinjiang,” May 2003,

http://news.xinhuanet.com/zhengfu/2003-06/12/content_916306.htm.

[3] This is the object of the debate between Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakyar. See Wang Lixiong, “Reflections on Tibet,”

art. cit., and the rebuttal: Tsering Shakyar, “Blood in the Snow,”

New Left Review, no. 15, May-June 2002. The gist of Tsering Shakyar’s argument is that Mao-worship in Tibet was no more blind than elsewhere in China, and that traditional Tibetan society remained dynamic and changing despite its religious characteristics. Woeser also documents the importance of the Mao-cult among Tibetans in

Shajie: Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution (Taipei, Dakuai wenhua, 2007).

[4] The “three inseparables” (

sange libukai) are: the Han cannot be separated from minorities, the minorities cannot be separated from the Han, and the minorities cannot be separated one from another. See: “Hu Jintao zai Zhongyang minzu gongzuo huiyi shang de jianghua” [Hu Jintao’s Speech at the Central Nationalities Working Committee], May 27, 2005,

http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1024/3423605.html (12 August 2008).

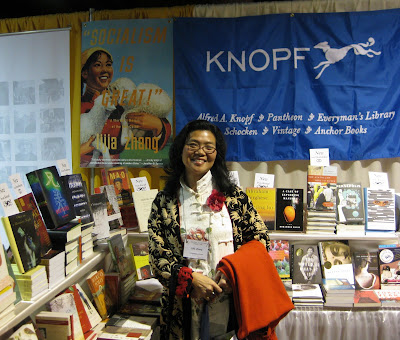

More than that, though, this is also a conference that, overall, has some features that run in tandem with some of the goals of China Beat. For example, just as we've tried to encourage more interchange between academics and other kinds of writers, there have been some sessions here that, thanks to generous support from the Luce Foundation, have already included or will include reporters and freelance writers. China Beat contributor Lijia Zhang (shown below posing with a poster for her memoir) and Ching-Ching Ni of the Los Angeles Times (shown below sharing her thoughts on the challenges of covering Chinese topics in the field), for example, were both part of a lively session on the Olympics, during which they shared the stage with Beijing-based specialist in Olympic studies Jin Yuanpu (shown below giving his presentation in Chinese), Susan Brownell (who did double duty as both moderator and Jin's translator), and Korea specialist Bruce Cumings (who gave a very smart summary of all the problems with thinking of the Seoul Games as a major contributing force in South Korea's democratization).

More than that, though, this is also a conference that, overall, has some features that run in tandem with some of the goals of China Beat. For example, just as we've tried to encourage more interchange between academics and other kinds of writers, there have been some sessions here that, thanks to generous support from the Luce Foundation, have already included or will include reporters and freelance writers. China Beat contributor Lijia Zhang (shown below posing with a poster for her memoir) and Ching-Ching Ni of the Los Angeles Times (shown below sharing her thoughts on the challenges of covering Chinese topics in the field), for example, were both part of a lively session on the Olympics, during which they shared the stage with Beijing-based specialist in Olympic studies Jin Yuanpu (shown below giving his presentation in Chinese), Susan Brownell (who did double duty as both moderator and Jin's translator), and Korea specialist Bruce Cumings (who gave a very smart summary of all the problems with thinking of the Seoul Games as a major contributing force in South Korea's democratization).